Legendary Military Martial Arts Instructor That Cannot Be Hit

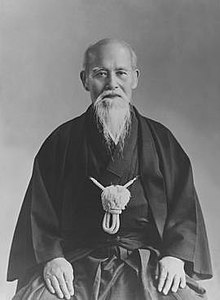

| Morihei Ueshiba | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | (1883-12-14)Dec 14, 1883 Tanabe, Wakayama, Japan |

| Died | April 26, 1969(1969-04-26) (anile 85) Iwama, Ibaraki, Nippon |

| Native name | 植芝 盛平 |

| Other names | Moritaka Ueshiba ( 植芝守高 ), Tsunemori ( 常盛 ) |

| Nationality | Japanese |

| Style | Aikido |

| Teacher(southward) | Takeda Sōkaku |

| Children |

|

| Notable students | see List of aikidoka |

Map of Japan showing the major locations in Ueshiba's life

Morihei Ueshiba ( 植芝 盛平 , Ueshiba Morihei , December xiv, 1883 – April 26, 1969) was a Japanese martial artist and founder of the martial fine art of aikido. He is ofttimes referred to equally "the founder" Kaiso ( 開祖 ) or Ōsensei ( 大先生/翁先生 ), "Bully Teacher".

The son of a landowner from Tanabe, Ueshiba studied a number of martial arts in his youth, and served in the Japanese Regular army during the Russo-Japanese War. Subsequently beingness discharged in 1907, he moved to Hokkaidō as the head of a pioneer settlement; here he met and studied with Takeda Sōkaku, the founder of Daitō-ryū Aiki-jūjutsu. On leaving Hokkaido in 1919, Ueshiba joined the Ōmoto-kyō movement, a Shinto sect, in Ayabe, where he served as a martial arts teacher and opened his first dojo. He accompanied the head of the Ōmoto-kyō grouping, Onisaburo Deguchi, on an expedition to Mongolia in 1924, where they were captured by Chinese troops and returned to Japan. The following yr, he had a profound spiritual experience, stating that, "a gilded spirit sprang upward from the ground, veiled my body, and changed my torso into a golden one." After this experience, his martial arts skill appeared to be greatly increased.

Ueshiba moved to Tokyo in 1926, where he set up what would become the Aikikai Hombu Dojo. By now he was insufficiently famous in martial arts circles, and taught at this dojo and others around Nihon, including in several armed services academies. In the backwash of World War Two the Hombu dojo was temporarily closed, but Ueshiba had past this point left Tokyo and retired to Iwama, and he continued training at the dojo he had fix up in that location. From the stop of the war until the 1960s, he worked to promote aikido throughout Nippon and abroad. He died from liver cancer in 1969.

Afterwards Ueshiba's death, aikido continued to be promulgated by his students (many of whom became noted martial artists in their own right). It is now practiced around the world.

Tanabe, 1883–1912 [edit]

Morihei Ueshiba was built-in in Nishinotani hamlet (now part of the city of Tanabe), Wakayama Prefecture, Japan, on Dec fourteen, 1883, the fourth child (and just son) born to Yoroku Ueshiba and his wife Yuki.[1] : 3 [ii] : 49

The young Ueshiba was raised in a somewhat privileged setting. His male parent Yoroku was a wealthy gentleman farmer and modest politician, being an elected member of the Nishinotani village council for 22 consecutive years. His mother Yuki was from the Itokawa clan, a prominent local family who could trace their lineage dorsum to the Heian period.[2] : 52–53 Ueshiba was a rather weak, sickly child and bookish in his inclinations. At a young age his begetter encouraged him to take up sumo wrestling and swimming and entertained him with stories of his groovy-granddad Kichiemon, who was considered a very strong samurai in his era. The need for such strength was further emphasized when the young Ueshiba witnessed his male parent being attacked by followers of a competing political leader.[three] : iii

A major influence on Ueshiba'southward early didactics was his elementary schoolteacher Tasaburo Nasu, who was a Shinto priest and who introduced Ueshiba to the religion.[2] : 59 At the age of half dozen Ueshiba was sent to study at the Jizōderu Temple, but had little involvement in the rote learning of Confucian education. However, his schoolmaster Mitsujo Fujimoto was as well a priest of Shingon Buddhism, and taught the immature Ueshiba some of the esoteric chants and ritual observances of the sect, which Ueshiba found intriguing. His involvement in Buddhism was sufficiently great that his mother considered enrolling him in the priesthood, but his father Yoroku vetoed the idea.[2] : 57 Ueshiba went to Tanabe Higher Elementary Schoolhouse and and then to Tanabe Prefectural Middle Schoolhouse, but left formal pedagogy in his early teens, enrolling instead at a individual abacus academy, the Yoshida Plant, to study accountancy.[2] : 61 On graduating from the academy, he worked at a local tax function for a few months, only the chore did non suit him and in 1901 he left for Tokyo, funded past his father. Ueshiba Trading, the jotter business which he opened in that location, was short-lived; unhappy with life in the capital, he returned to Tanabe less than a year later afterwards suffering a bout of beri-beri. Shortly thereafter he married his childhood acquaintance Hatsu Itokawa.[iv] [5]

In 1903, Ueshiba was called upwardly for military service. He failed the initial physical test, existence shorter than the regulation 5 feet two inches (1.57 one thousand). To overcome this, he stretched his spine by attaching heavy weights to his legs and suspending himself from tree branches; when he re-took the physical examination he had increased his height by the necessary one-half-inch to laissez passer.[iv] He was assigned to the Osaka Quaternary Sectionalisation, 37th Regiment, and was promoted to corporal of the 61st Wakayama regiment by the following year; afterward serving on the forepart lines during the Russo-Japanese State of war he was promoted to sergeant.[2] : 70 He was discharged in 1907, and again returned to his begetter's farm in Tanabe.[five] Here he befriended the writer and philosopher Minakata Kumagusu, becoming involved with Minakata's opposition to the Meiji government'southward Shrine Consolidation Policy.[iv] He and his wife had their first child, a girl named Matsuko, in 1911.[vi] : 3

Ueshiba studied several martial arts during his early life, and was renowned for his physical strength during his youth.[7] During his sojourn in Tokyo he studied Kitō-ryū jujutsu under Takisaburo Tobari, and briefly enrolled in a school teaching Shinkage-ryū.[two] : 64–65 His preparation in Gotō-ha Yagyū-ryu under Masakatsu Nakai started in 1903 and continued until 1908, though was sporadic due to his military service, yet he was granted a Menkyo Kaiden (certificate of "Total Transmission") in 1908.[iv] In 1901 he received some didactics from Tozawa Tokusaburōin in Tenjin Shin'yō-ryū jujutsu and he studied judo with Kiyoichi Takagi in Tanabe in 1911, after his begetter had a dojo built on the family compound to encourage his son'due south training.[five] In 1907, afterwards his return from the war, he was also presented with a certificate of enlightenment (shingon inkyo) by his childhood instructor Mitsujo Fujimoto.[two] : 66

Hokkaidō, 1912–1920 [edit]

Morihei Ueshiba at effectually 35 years sometime (1918)

In the early part of the 20th century, the prefectural authorities of Hokkaidō, Japan'southward northernmost island, were offering various grants and incentives for mainland Japanese groups willing to relocate in that location. At the time, Hokkaidō was still largely unsettled by the Japanese, being occupied primarily by the ethnic Ainu. In 1910, Ueshiba travelled to Hokkaidō in the company of his acquaintance Denzaburo Kurahashi, who had lived on the northern island earlier. His intent was to scout out a propitious location for a new settlement, and he constitute the site at Shirataki suitable for his plans. Despite the hardships he suffered on this journey (which included getting lost in snowstorms several times and an incident in which he nearly drowned in a freezing river), Ueshiba returned to Tanabe filled with enthusiasm for the project, and began recruiting families to join him. He became the leader of the Kishū Settlement Group, a collective of eighty-five pioneers who intended to settle in the Shirataki district and live as farmers; the grouping founded the village of Yubetsu (after Shirataki village) in August, 1912.[2] : 83–87 Much of the funding for this project came from Ueshiba's father and his brothers-in-police Zenzo and Koshiro Inoue. Zenzo'south son Noriaki was also a member of the settlement grouping.[8]

Poor soil weather condition and bad conditions led to ingather failures during the first three years of the project, but the group still managed to cultivate mint and subcontract livestock. The burgeoning timber industry provided a boost to the settlement'due south economy, and past 1918 there were over 500 families residing in that location.[2] : 101 A burn down in 1917 razed the unabridged village, leading to the deviation of around 20 families. Ueshiba was attention a coming together over railway structure around 50 miles away, simply on learning of the fire travelled back the entire distance on foot. He was elected to the village council that yr, and took a prominent part in leading the reconstruction efforts.[ii] : 101–103 In the summer of 1918, Hatsu gave birth to their start son, Takemori.[4] [five]

The young Ueshiba met Takeda Sōkaku, the founder of Daitō-ryū Aiki-jūjutsu, at the Hisada Inn in Engaru, in March 1915. Ueshiba was securely impressed with Takeda'due south martial art, and despite being on an important mission for his village at the time, abandoned his journey to spend the next month studying with Takeda.[2] : 94 He requested formal instruction and began studying Takeda's style of jūjutsu in earnest, going so far equally to construct a dojo at his domicile and inviting his new teacher to be a permanent firm guest.[nine] : 22 [x] He received a kyōju dairi certificate, a educational activity license, for the organization from Takeda in 1922, when Takeda visited him in Ayabe.[9] : 36 Takeda also gave him a Yagyū Shinkage-ryū sword manual scroll.[eleven] Ueshiba so became a representative of Daitō-ryū, toured with Takeda as a instruction assistant and taught the organization to others.[12] [thirteen] The relationship betwixt Ueshiba and Takeda was a complicated i. Ueshiba was an extremely defended student, dutifully attention to his instructor's needs and displaying slap-up respect. However, Takeda overshadowed him throughout his early martial arts career, and Ueshiba's own students recorded the need to address what they referred to equally "the Takeda problem".[12] [fourteen] : 137–139 [15]

Ayabe, 1920–1927 [edit]

In November 1919, Ueshiba learned that his father Yoroku was ill, and was not expected to survive. Leaving nearly of his possessions to Takeda, Ueshiba left Shirataki with the credible intention of returning to Tanabe to visit his bilious parent. En route he made a detour to Ayabe, virtually Kyoto, intending to visit Onisaburo Deguchi, the spiritual leader of the Ōmoto-kyō religion (Ueshiba's nephew Noriaki Inoue had already joined the religion and may have recommended it to his uncle).[8] Ueshiba stayed at the Ōmoto-kyō headquarters for several days, and met with Deguchi, who told him that, "At that place is nothing to worry about with your begetter".[2] : 113 On his return to Tanabe, Ueshiba plant that Yoroku had died. Criticised by family unit and friends for arriving besides late to come across his father, Ueshiba went into the mountains with a sword and practised solo sword exercises for several days; this almost led to his arrest when the police were informed of a sword-wielding madman on the loose.[ii] : 116

Within a few months, Ueshiba was dorsum in Ayabe, having decided to become a full-time student of Ōmoto-kyō. In 1920 he moved his entire family unit, including his female parent, to the Ōmoto compound; at the same fourth dimension he also purchased enough rice to feed himself and his family for several years.[ii] : 117 That aforementioned year, Deguchi asked Ueshiba to become the grouping's martial arts teacher, and a dojo—the commencement of several that Ueshiba was to lead—was constructed on the center's grounds. Ueshiba likewise taught Takeda's Daitō-ryū in neighbouring Hyōgo Prefecture during this menstruation.[16] His second son, Kuniharu, was born in 1920 in Ayabe, just died from affliction the same twelvemonth, forth with 3-year-old Takemori.[nine] : 32–34

Takeda visited Ueshiba in Ayabe to provide instruction, although he was non a follower of Ōmoto and did not get along with Deguchi, which led to a cooling of the relationship betwixt him and Ueshiba.[15] Ueshiba continued to teach his martial art nether the name "Daitō-ryū Aiki-jūjutsu", at the behest of his teacher.[17] However, Deguchi encouraged Ueshiba to create his own fashion of martial arts, "Ueshiba-ryū", and sent many Ōmoto followers to study at the dojo. He also brought Ueshiba into the highest levels of the group'southward hierarchy, making Ueshiba his executive assistant and putting him in accuse of the Showa Seinenkai (Ōmoto-kyō's national youth organisation) and the Ōmoto Shobotai, a volunteer fire service.[2] : 118, 128, 137

His close human relationship with Deguchi introduced Ueshiba to various members of Japan's far-right; members of the ultranationalist group the Sakurakai would hold meetings at Ueshiba'southward dojo, and he developed a friendship with the philosopher Shūmei Ōkawa during this period, besides every bit meeting with Nisshō Inoue and Kozaburō Tachibana. Deguchi too offered Ueshiba's services as a bodyguard to Kingoro Hashimoto, the Sakurakai's founder.[fourteen] : 142–149 [xviii] Ueshiba's commitment to the goal of world peace, stressed past many biographers, must be viewed in the light of these relationships and his Ōmoto-kyō beliefs. His clan with the extreme correct-wing is understandable when i considers that Ōmoto-kyō's view of world peace was of a benevolent dictatorship by the Emperor of Nihon, with other nations beingness subjugated under Japanese rule.[nineteen] : 638–639

In 1921, in an event known as the Start Ōmoto-kyō Incident ( 大本事件 , Ōmoto jiken ), the Japanese authorities raided the chemical compound, destroying the master buildings on the site and arresting Deguchi on charges of lèse-majesté.[xx] Ueshiba's dojo was undamaged and over the following ii years he worked closely with Deguchi to reconstruct the group'due south centre, becoming heavily involved in farming work and serving as the group'south "Caretaker of Forms", a role which placed him in charge of overseeing Ōmoto'due south movement towards self-sufficiency.[two] : 154 His son Kisshomaru was born in the summer of 1921.[v] [ix] : 32–34

3 years later on, in 1924, Deguchi led a small grouping of Ōmoto-kyō disciples, including Ueshiba, on a journeying to Mongolia at the invitation of retired naval helm Yutaro Yano and his associates within the ultra-nationalist Black Dragon Order. Deguchi's intent was to establish a new religious kingdom in Mongolia, and to this end he had distributed propaganda suggesting that he was the reincarnation of Genghis Khan.[21] Centrolineal with the Mongolian brigand Lu Zhankui, Deguchi's group were arrested in Tongliao past the Chinese authorities—fortunately for Ueshiba, whilst Lu and his men were executed past firing team, the Japanese group were released into the custody of the Japanese consul. They were returned under guard to Japan, where Deguchi was imprisoned for breaking the terms of his bond.[9] : 37–45 During this expedition Ueshiba was given the Chinese allonym Wang Shou-gao, rendered in Japanese as "Moritaka" – he was reportedly very taken with this proper noun and connected to use it intermittently for the rest of his life.[2] : 163

After returning to Ayabe, Ueshiba began a regimen of spiritual grooming, regularly retreating to the mountains or performing misogi in the Nachi Falls. As his prowess every bit a martial creative person increased, his fame began to spread. He was challenged past many established martial artists, some of whom later became his students later on existence defeated by him. In the autumn of 1925 he was asked to give a demonstration of his art in Tokyo, at the behest of Admiral Isamu Takeshita; one of the spectators was Yamamoto Gonnohyōe, who requested that Ueshiba stay in the uppercase to instruct the Majestic Guard in his martial art. Afterwards a couple of weeks, however, Ueshiba took consequence with several government officials who voiced concerns nigh his connections to Deguchi; he cancelled the training and returned to Ayabe.[9] : 45–49

Tokyo, 1927–1942 [edit]

In 1926 Takeshita invited Ueshiba to visit Tokyo again. Ueshiba relented and returned to the capital, but while residing there was stricken with a serious illness. Deguchi visited his ailing student and, concerned for his wellness, commanded Ueshiba to render to Ayabe. The entreatment of returning increased afterward Ueshiba was questioned past the police post-obit his meeting with Deguchi; the authorities were keeping the Ōmoto-kyō leader under close surveillance. Angered at the treatment he had received, Ueshiba went back to Ayabe once again. Half dozen months subsequently, this fourth dimension with Deguchi's blessing, he and his family unit moved permanently to Tokyo. This move immune Ueshiba to teach politicians, high-ranking military personnel, and members of the Majestic household; suddenly he was no longer an obscure provincial martial creative person, but a sensei to some of Japan'due south nigh important citizens.[19] : 134 Arriving in Oct 1927, the Ueshiba family ready habitation in the Shirokane commune. The building proved too pocket-size to firm the growing number of aikido students, and so the Ueshibas moved to larger premises, offset in Mita district, then in Takanawa, and finally to a purpose-built hall in Shinjuku. This final location, originally named the Kobukan ( 皇武館 ), would eventually become the Aikikai Hombu Dojo. During its construction, Ueshiba rented a property nearby, where he was visited by Kanō Jigorō, the founder of judo.[9] : fifty–53

During this period, Ueshiba was invited to teach at a number of military machine institutes, due to his close personal relationships with key figures in the military (among them Sadao Araki, the Japanese Minister of War[19] : 639 ). He accustomed an invitation from Admiral Sankichi Takahashi to be the martial arts instructor at the Royal Japanese Naval Academy,[ii] : 201 and likewise taught at the Nakano Spy Schoolhouse, although aikido was later judged to be too technical for the students there and karate was adopted instead.[14] : 154–155 He too became a visiting instructor at the Imperial Japanese Regular army University after existence challenged by (and defeating) General Makoto Miura, some other student of Takeda Sōkaku's Daitō-ryū.[ii] : 207–208 [19] : 639 Takeda himself met Ueshiba for the concluding fourth dimension around 1935, while Ueshiba was teaching at the Osaka headquarters of the Asahi Shimbun newspaper. Frustrated past the appearance of his teacher, who was openly critical of Ueshiba's martial arts and who appeared intent on taking over the classes there, Ueshiba left Osaka during the night, bowing to the residence in which Takeda was staying and thereafter avoiding all contact with him.[xiv] : 139 [19] : 135 Between 1940 and 1942 he fabricated several visits to Manchukuo (Japanese occupied Manchuria) where he was the main martial arts instructor at Kenkoku Academy.[nine] : 63 Whilst in Manchuria, he met and defeated the sumo wrestler Tenryū Saburō during a sit-in.[22]

The "Second Ōmoto Incident" in 1935 saw another government crackdown on Deguchi'due south sect, in which the Ayabe compound was destroyed and most of the group's leaders imprisoned. Although he had relocated to Tokyo, Ueshiba had retained links with the Ōmoto-kyō group (he had in fact helped Deguchi to found a paramilitary co-operative of the sect only three years before[19] : 134 ) and expected to be arrested as ane of its senior members. Even so, he had a skilful relationship with the local police commissioner Kenji Tomita and the master of law Gīchi Morita, both of whom had been his students. As a result, although he was taken in for interrogation, he was released without charge on Morita'southward authority.[2] : 233–237

In 1932, Ueshiba's daughter Matsuko was married to the swordsman Kiyoshi Nakakura, who was adopted every bit Ueshiba's heir under the name Morihiro Ueshiba. The marriage concluded after a few years, and Nakakura left the family unit in 1937. Ueshiba later designated his son Kisshomaru as the heir to his martial art.[23] [19] : 134

The 1930s saw Japan'south invasion of mainland Asia and increased military activity in Europe. Ueshiba was concerned about the prospect of war, and became involved in a number of efforts to try and forestall the conflict that would somewhen become World War II. He was function of a grouping, forth with Shūmei Ōkawa and several wealthy Japanese backers, that tried to broker a deal with Harry Chandler to export aviation fuel from the The states to Japan (in contravention of the oil embargo that was currently in strength), although this endeavor ultimately failed.[fourteen] : 156 In 1941 Ueshiba also undertook a secret diplomatic mission to Red china at the behest of Prince Fumimaro Konoe. The intended goal was a meeting with Chiang Kai-shek to establish peace talks, but Ueshiba was unable to meet with the Chinese leader, arriving too tardily to fulfil his mission.[2] : 236–237

Iwama, 1942–1969 [edit]

From 1935 onwards, Ueshiba had been purchasing land in Iwama in Ibaraki Prefecture, and by the early on 1940s had acquired around 17 acres (6.9 ha; 0.027 sq mi) of farmland at that place. In 1942, disenchanted with the war-mongering and political manoeuvring in the upper-case letter, he left Tokyo and moved to Iwama permanently, settling in a small farmer's cottage.[19] : 639 Here he founded the Aiki Shuren Dojo, as well known equally the Iwama dojo, and the Aiki Shrine, a devotional shrine to the "Slap-up Spirit of Aiki".[24] [5] [nine] : 55 During this fourth dimension he travelled extensively in Japan, particularly in the Kansai region, teaching his aikido. Despite the prohibition on the teaching of martial arts later Earth War II, Ueshiba and his students continued to practice in clandestine at the Iwama dojo; the Hombu dojo in Tokyo was in whatsoever case existence used equally a refugee centre for citizens displaced by the severe firebombing. Information technology was during this period that Ueshiba met and befriended Koun Nakanishi, an expert in kotodama. The study of kotodama was to become one of Ueshiba's passions in afterward life, and Nakanishi's work inspired Ueshiba's concept of takemusu aiki.[2] : 267

The rural nature of his new habitation in Iwama allowed Ueshiba to concentrate on the second great passion of his life: farming. He had been born into a farming family unit and spent much of his life cultivating the land, from his settlement days in Hokkaidō to his piece of work in Ayabe trying to make the Ōmoto-kyō chemical compound self-sufficient. He viewed farming as a logical complement to martial arts; both were physically demanding and required single-minded dedication. Not only did his farming activities provide a useful encompass for martial arts grooming under the government'due south restrictions, it also provided nutrient for Ueshiba, his students and other local families at a time when food shortages were commonplace.[i] : 18–xix [19] : 135

Ikkyo, first principle established between the founder Sensei Morihei Ueshiba (植芝 盛平, Dec xiv, 1883 – Apr 26, 1969) and André Nocquet (30 July 1914 – 12 March 1999[25]) disciple.

The regime prohibition (on aikido, at least) was lifted in 1948 with the cosmos of the Aiki Foundation, established by the Japanese Ministry of Education with permission from the Occupation forces. The Hombu dojo re-opened the following year. After the state of war Ueshiba finer retired from aikido.[26] He delegated nearly of the work of running the Hombu dojo and the Aiki Federation to his son Kisshomaru, and instead chose to spend much of his time in prayer, meditation, calligraphy and farming.[ix] : 66–69 He still travelled extensively to promote aikido, even visiting Hawaii in 1961.[iv] : xix He as well appeared in a television documentary on aikido: NTV'southward The Master of Aikido, broadcast in January 1960.[5] Ueshiba maintained links with the Japanese nationalist movement even in later life; his student Kanshu Sunadomari reported that Ueshiba temporarily sheltered Mikami Taku, one of the naval officers involved in the May 15 Incident, at Iwama.[14] : 159–160

In 1969, Ueshiba became ill. He led his final preparation session on March 10, and was taken to hospital where he was diagnosed with cancer of the liver. He died suddenly on Apr 26, 1969.[9] : 72 His body was buried at Kozan-ji Temple Tanabe-shi Wakayama Japan, and he was given the posthumous Buddhist title "Aiki-in Moritake En'yū Daidōshi" ( 合気院盛武円融大道士 ); parts of his hair were enshrined at Ayabe, Iwama and Kumano.[3] : thirteen Two months later, his wife Hatsu ( 植芝 はつ Ueshiba Hatsu, née Itokawa Hatsu; 1881–1969) also died.[2] : 316–317 [6] : 3

Evolution of aikido [edit]

Aikido—normally translated as the Way of Unifying Spirit or the Manner of Spiritual Harmony—is a fighting system that focuses on throws, pins and joint locks together with some hit techniques. Information technology emphasises protecting the opponent and promotes spiritual and social development.[27]

The technical curriculum of aikido was derived from the teachings of Takeda Sōkaku; the basic techniques of aikido stem from his Daitō-ryū organisation.[12] [28] In the earlier years of his teaching, from the 1920s to the mid-1930s, Ueshiba taught the Daitō-ryū Aiki-jūjutsu organisation; his early students' documents bear the term Daitō-ryū.[15] Indeed, Ueshiba trained one of the hereafter highest grade earners in Daitō-ryū, Takuma Hisa, in the art before Takeda took accuse of Hisa'southward grooming.[29]

The early form of preparation under Ueshiba was noticeably different from later forms of aikido. It had a larger curriculum, increased utilise of strikes to vital points (atemi) and a greater employ of weapons. The schools of aikido developed past Ueshiba'southward students from the pre-war period tend to reflect the harder style of the early grooming. These students included Kenji Tomiki (who founded the Shodokan Aikido sometimes chosen Tomiki-ryū), Noriaki Inoue (who founded Shin'ei Taidō), Minoru Mochizuki (who founded Yoseikan Budo) and Gozo Shioda (who founded Yoshinkan Aikido). Many of these styles are therefore considered "pre-war styles", although some of these teachers continued to train with Ueshiba in the years after World State of war II.[19] : 134–136

During his lifetime, Ueshiba had 3 spiritual experiences that impacted greatly on his understanding of the martial arts. The beginning occurred in 1925, after Ueshiba had defeated a naval officer's bokken (wooden katana) attacks unarmed and without hurting the officer. Ueshiba and then walked to his garden, where he had the post-obit realisation:

I felt the universe suddenly quake, and that a gilded spirit sprang upwardly from the ground, veiled my body, and inverse my body into a golden 1. At the same time my body became light. I was able to sympathize the whispering of the birds, and was conspicuously aware of the mind of God, the creator of the universe. At that moment I was enlightened: the source of budō [the martial style] is God's love – the spirit of loving protection for all beings ... Budō is not the felling of an opponent by force; nor is it a tool to lead the world to destruction with arms. True Budō is to have the spirit of the universe, proceed the peace of the world, correctly produce, protect and cultivate all beings in nature.[30]

His second experience occurred in 1940 when engaged in the ritual purification process of misogi.

Effectually 2 am, I suddenly forgot all the martial techniques I had ever learned. The techniques of my teachers appeared completely new. Now they were vehicles for the cultivation of life, knowledge, and virtue, not devices to throw people with.[31]

His third experience was in 1942 during the worst fighting of World State of war II, when Ueshiba had a vision of the "Groovy Spirit of Peace".[1] : 18

The Mode of the Warrior has been misunderstood. It is not a means to kill and destroy others. Those who seek to compete and amend ane some other are making a terrible mistake. To smash, injure, or destroy is the worst thing a homo being can do. The existent Way of a Warrior is to foreclose such slaughter – it is the Art of Peace, the ability of beloved.[32] : 223

After these events, Ueshiba seemed to slowly abound away from Takeda, and he began to change his art.[33] These changes are reflected in the differing names with which he referred to his system, first as aiki-jūjutsu, then Ueshiba-ryū, Asahi-ryū,[34] and aiki budō.[32] : 89 In 1942, when Ueshiba's grouping joined the Dai Nippon Butoku Kai, the martial fine art that Ueshiba developed finally came to be known as aikido.[xvi] [35] [36]

Equally Ueshiba grew older, more skilled, and more spiritual in his outlook, his art also inverse and became softer and more gentle. Martial techniques became less important, and more focus was given to the control of ki.[37] [38] In his own expression of the fine art in that location was a greater emphasis on what is referred to every bit kokyū-nage, or "breath throws" which are soft and blending, utilizing the opponent's motility in order to throw them. Ueshiba regularly practiced cold h2o misogi, as well equally other spiritual and religious rites, and viewed his studies of aikido as office of this spiritual preparation.[6] : 17

Ueshiba with a grouping of his international students at the Hombu dojo in 1967.

Over the years, Ueshiba trained a big number of students, many of whom later became famous teachers in their own right and developed their own styles of aikido. Some of them were uchi-deshi, live-in students. Ueshiba placed many demands on his uchi-deshi, expecting them to attend him at all times, act as preparation partners (even in the heart of the night), arrange his travel plans, massage and breast-stroke him, and aid with household chores.[39]

There were roughly four generations of students, comprising the pre-war students (grooming c.1921–1935), students who trained during the Second Globe War (c.1936–1945), the post-war students in Iwama (c.1946–1955) and the students who trained with Ueshiba during his last years (c.1956–c.1969).[ten] As a result of Ueshiba'southward martial development throughout his life, students from each of these generations tend to have markedly dissimilar approaches to aikido.[39] These variations are compounded by the fact that few students trained with Ueshiba for a protracted period; merely Yoichiro Inoue, Kenji Tomiki, Gozo Shioda, Morihiro Saito, Tsutomu Yukawa and Mitsugi Saotome studied direct nether Ueshiba for more than than 5 or six years.[26] [40] After the war, Ueshiba and the Hombu Dojo dispatched some of their students to various other countries, resulting in aikido spreading around the globe.[41] [19] : 136

Honors [edit]

- Medal of Award (Purple Ribbon) (Nippon), 1960[2] : 306

- Order of the Rise Dominicus, Gold Rays with Rosette, 1964[42] [2] : 309

- Order of the Sacred Treasure (Nippon), 1968[43]

Works [edit]

- Morihei Ueshiba, The Clandestine Teachings of Aikido (2008), Kodansha International, ISBN 978-4-7700-3030-half-dozen

- Morihei Ueshiba, Budo: Teachings of the Founder of Aikido (1996), Kodansha International, ISBN 978-4-7700-2070-three

- Morihei Ueshiba, The Essence of Aikido: Spiritual Teachings of Morihei Ueshiba (1998), Kodansha International, ISBN 978-iv-7700-2357-5

- Morihei Ueshiba, The Fine art of Peace (2007), Shambhala, ISBN 978-1590304488 - selection from Morihei's talks, poems, calligraphy and oral tradition, including extract from Budo, Aikido: The Spiritual Dimension, and Aiki Shinzui compiled and translated by John Stevens[i]

References [edit]

- ^ a b c d Ueshiba, Morihei (3 December 2002). The Art of Peace. Translated by Stevens, John. Shambhala Publications. ISBN978-0-8348-2168-ii.

- ^ a b c d eastward f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u five w x y z Ueshiba, Kisshomaru (2008). A Life in Aikido: The Biography of Founder Morihei Ueshiba. New York: Kodansha. ISBN978-1-56836-573-two.

- ^ a b Stevens, John; Shirata, Rinjiro (1984). Aikido; the Mode of Harmony. Boston: Shambhala Publications. ISBN978-0-394-71426-4.

- ^ a b c d e f Stevens, John; Krenner, Walther (2004). Grooming with the Master: Lessons with Morihei Ueshiba, Founder of Aikido. Boston & London: Shambhala. pp. nine–xxii. ISBN978-1-57062-568-8.

- ^ a b c d east f 1000 Ueshiba, Kisshomaru; Ueshiba, Morihei (1996). "Introduction". Budo: Teachings of the Founder of Aikido. Tokyo, New York, London: Kodansha International. pp. 8–23. ISBN4-7700-2070-8.

- ^ a b c Dang, Phong Thong; Seiser, Lynn (2006). Avant-garde Aikido. Tuttle Publishing. p. 3. ISBN978-0-8048-3785-nine.

- ^ Stone, J; Myer, R (1995). Aikido in America. Frog Books. p. two. ISBN978-1-883319-27-four.

- ^ a b Pranin, Stanley. "The "Co-founder of Aikido" Ignored past History". Aikido Periodical. Aikido Journal. Retrieved 27 Feb 2017.

- ^ a b c d east f 1000 h i j 1000 Stevens, John (1999). Invincible Warrior: A Pictorial Biography of Morihe Ueshiba, the Founder of Aikido. Boston, London: Shambhala. ISBN978-1-57062-394-iii.

- ^ a b Pranin, Stanley (2006). "Interview with Kisshomaru and Morihei Ueshiba". Aikidojournal.com. Retrieved 4 August 2014.

- ^ Amdur, Ellis. "Errata from Hidden in Plain Sight" (PDF) . Retrieved 25 July 2014.

- ^ a b c Schaefer, Jean. "The Morihei Ueshiba Biography: From Sumo to Aikido". Black Belt. Cruz Bay Publishing. Archived from the original on 2016-12-sixteen. Retrieved 27 February 2017.

- ^ Nelson, Gail E. (February 1986). "Aikijujutsu vs. Aikido". Black Belt Magazine. 24 (2): 34–38. Retrieved 27 Feb 2017.

- ^ a b c d east f Amdur, Ellis (2017). Duelling with O-sensei: Grappling with the Myth of the Warrior Sage (Revised Expanded Edition 2017 ed.). Wheaton, IL: Freelance Academy Press. ISBN978-1-937439-24-8.

- ^ a b c Pranin, Stanley. "The dear-detest relationship between Morihei Ueshiba and Sōkaku Takeda". Aikido Journal. Aikido Journal. Retrieved 1 March 2017.

- ^ a b Guttmann, Allen; Thompson, Lee Austin (January 2001). Japanese Sports: A History. University of Hawaii Press. pp. 148–149. ISBN978-0-8248-2464-8.

- ^ Pranin, Stanley. "Historical photograph: "The amazing chameleon photo of O-Sensei from 1922,"". Aikido Periodical. Aikido Journal. Archived from the original on ane March 2017. Retrieved 28 Feb 2017.

- ^ Pranin, Stanley (2010). Aikido Pioneers – Prewar Era: Interviews with 20 of the Top Students of Aikido Founder Morihei Ueshiba. Aiki News. ISBN978-four-904464-17-v.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j grand Green, Thomas A.; Svinth, Joseph R. (11 June 2010). Martial Arts of the Earth: An Encyclopedia of History and Innovation [2 volumes]. ABC-CLIO. ISBN978-i-59884-244-9.

- ^ Offner, Clark B.; Straelen, Henricus Johannes Josephus Maria (1963). Modern Japanese Religions: With Special Emphasis Upon Their Doctrines of Healing. Brill Archive. p. 69. GGKEY:RH5B37ENWUL.

- ^ Bulag, Uradyn Due east. (xvi July 2010). Collaborative Nationalism: The Politics of Friendship on Mainland china's Mongolian Frontier. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. p. 41. ISBN978-1-4422-0433-one.

- ^ Pranin, Stanley. "Sumo champion Tenryu and Morihei Ueshiba". Aikido Journal. Aikido Periodical. Retrieved 28 Feb 2017.

- ^ Pranin, Stanley. "Focus on History: Ueshiba Family Tree: The Line of Succession". Screencast. Aikido Journal. Retrieved 26 June 2013.

- ^ Strozzi-Heckler, Richard (1985). Aikido and the New Warrior . North Atlantic Books. p. 21. ISBN978-0-938190-51-6.

- ^ "Foundation of the Covenant". 2020-eleven-21.

- ^ a b Pranin, Stanley. "Is O-Sensei Really the Father of Modern Aikido?". Aikido Periodical. Aikido Periodical. Archived from the original on 4 March 2017. Retrieved 24 March 2017.

- ^ Westbrook, Adele; Ratti, Oscar (1 July 2001). Aikido and the Dynamic Sphere: An Illustrated Introduction. Tuttle Publishing. pp. 17–20. ISBN978-0-8048-3284-seven.

- ^ Pranin, Stanley. "From Aikijujutsu to Aikido! Where did it come up from ... how did information technology evolve?". Aikido Periodical. Aikido Journal. Archived from the original on 21 September 2017. Retrieved 27 February 2017.

- ^ Pranin, Stanley. "Historical photograph: "Takuma Hisa, the bridge between Daito-ryu and Aiki Budo,"". Aikido Journal. Aikido Journal. Archived from the original on 27 February 2017. Retrieved 27 February 2017.

- ^ Ueshiba, Kisshomaru (1985). Aikido. Tokyo: Hozansha Publications.

- ^ Nepo, Marker (xiv July 2015). The Endless Do: Condign Who You Were Born to Be. Simon and Schuster. pp. 302–303. ISBN978-1-4767-7466-iv.

- ^ a b Wagner, Winfried (nineteen June 2015). AiKiDô: The Trinity of Conflict Transformation. Springer. ISBN978-iii-658-10166-4.

- ^ Donohue, John (iv November 2004). The Overlook Martial Arts Reader . Overlook Press. p. 90. ISBN978-1-58567-463-three.

- ^ Takeda, Tokimune (2006). "Sōkaku Takeda in Osaka". Aikidojournal.com. Archived from the original on 5 June 2011. Retrieved 4 August 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Saunders, Neil (2003). Aikido: The Tomiki Way. Trafford Publishing. p. viii. ISBN978-1-4120-0668-2.

- ^ Bennett, Alexander C. (31 July 2015). Kendo: Culture of the Sword. Univ of California Press. p. 12. ISBN978-0-520-28437-ane.

- ^ Ohama, Gary. "Ueshiba and Timing: Pre-War vs. Mail-State of war Technique". Aikido Journal. Aikido Journal. Archived from the original on xv March 2017. Retrieved xiv March 2017.

- ^ Von Krenner, Walther 1000.; Apodaca, Damon; Jeremiah, Ken (14 May 2013). Aikido Ground Fighting: Grappling and Submission Techniques. North Atlantic Books. p. xviii. ISBN978-ane-58394-621-3.

- ^ a b Perry, Susan (12 November 2002). Remembering O-Sensei: Living and Preparation with Morihei Ueshiba, Founder of Aikido. Shambhala. p. xiv–fifteen. ISBN978-0-8348-2946-6.

- ^ Pranin, Stanley. "When Koichi Tohei and Morihiro Saito met for the last time… October 29, 2001". Aikido Journal. Aikido Journal. Archived from the original on 22 June 2017. Retrieved 29 March 2017.

- ^ Stevens, John (9 July 1996). The Shambhala Guide to Aikido. Shambhala. p. 27. ISBN978-0-8348-0010-six.

- ^ "Japanese Govt. Decorates Aikido Master Uyeshiba". Black Belt. 3 (7): 50. July 1965. ISSN 0277-3066. Retrieved iv April 2017.

- ^ "Fifty'ORDRE DU TRÉSOR SACRÉ (JAPON)" (in French). L'Harmattan. Retrieved 4 August 2014.

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Morihei_Ueshiba

0 Response to "Legendary Military Martial Arts Instructor That Cannot Be Hit"

Enviar um comentário